Seizing the Opportunity to Advance City Contracting Equity

2020 Bureau of Contract Administration

Report

Los Angeles spends billions of dollars yearly on contracts for commodities, professional services and construction. The City’s purchasing power presents a tremendous opportunity to invest in local small businesses, and businesses owned by women and people of color, but Los Angeles is not as effective as it could be in connecting small businesses and businesses owned by historically disadvantaged groups to contracting opportunities. This report identifies ways the City of Los Angeles can better assist businesses and improve contracting equity.

Each bar below contains a section of the report. Click on any to expand and read the full text of the section. Click again to collapse.

July 8, 2020

Honorable Eric Garcetti, Mayor

Honorable Michael Feuer, City Attorney

Honorable Members of the Los Angeles City Council

Re: Seizing the Opportunity to Advance City Contracting Equity

Unprecedented events have defined 2020 thus far: first, a global pandemic virtually shut down our economy for months; then, during the shutdown, a widespread uprising against racial injustice, fueled by the killing of George Floyd, captivated the national consciousness and started a deep and necessary dialogue within this and other local governments over how to best confront systemic racism that is still very much entrenched in our society. While these two major happenings have different causes and effects, together they shone a spotlight squarely on economic and social issues.

In response, the City of Los Angeles has taken a series of meaningful legislative and executive actions, aiming to help small community businesses survive the coronavirus shutdown and filling the gaps left by the federal government. Addressing issues of equity, officials have responded to community budget priorities and worked to create new structures in an effort to enhance inclusion. My latest review directly aligns with these efforts as it identifies ways Los Angeles can better assist businesses and improve equity — through the City’s inclusionary contracting programs and procedures.

Ineffective mechanisms for inclusion

Los Angeles spends billions of dollars yearly on contracts for commodities, professional services and construction. The City’s purchasing power presents a tremendous opportunity to invest in local small businesses, and businesses owned by women and people of color. There are approximately 6,000 firms certified under these and other categories within the City’s contracting database. The City’s main mechanism for connecting small and disadvantaged businesses to contracting opportunities is the Business Inclusion Program (BIP), which requires firms competing for contracts to reach out to a minimum number of certified firms and make a good faith effort to develop more inclusionary subcontracting opportunities.

However, BIP could be more effective at connecting small businesses and businesses owned by historically disadvantaged groups. The City’s fragmented and decentralized procurement process makes this and similar investment programs exceedingly difficult to administer. Despite directives requiring departments to track and report on the participation of certified firms in City contracting, the data has not been adequately analyzed to date. Without this crucial information, it is impossible to determine which groups are underrepresented and eliminate barriers to their participation. Additionally, as a result of restrictions imposed by state law, the City’s strategy for connecting certified firms with contracting opportunities rests on simply urging large firms to partner with local small businesses and firms owned by women, people of color, disabled veterans and others without a mandate to do so.

There are precedents for a more equitable way forward. The City’s proprietary departments — the Port of Los Angeles, Los Angeles World Airports and the Department of Water and Power — have already implemented small business participation programs and seen substantial increases in the number of small businesses working on department contracts. And it is possible that the City’s contracting environment will change significantly if California voters decide to remove restrictions that prevent race- or gender-based contracting preferences.

Investing in the local business community

Regardless of what happens at the ballot box, we have the ability today to rethink the City’s approach to business inclusion to both spur economic opportunity and enhance contracting equity. My report makes the following recommendations:

- Establish a pilot program requiring small business participation in large City contracts.

- Redesign the BIP outreach process to promote outreach to certified firms, small businesses, local businesses, and businesses owned by women and people of color.

- Identify or establish a City department or working group with the resources and authority to monitor and enforce BIP requirements.

- Standardize BIP data collection and reporting by City departments and publish the findings online.

- Develop a mentor-protégé program where experienced prime contractors provide technical training and guidance to smaller firms.

I urge City leaders to adopt these recommendations to ensure that our City does everything it can to support our local small businesses, and those owned by women and people of color. Working together with the local business community, we can seize the opportunity before us and create a more equitable and inclusive future.

Respectfully submitted,

RON GALPERIN

L.A. Controller

Supporting Los Angeles businesses – especially the diverse small business community – is essential as we work to recover from the devastating impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. These businesses are especially vulnerable in the aftermath of an economic shock, and the City has taken proactive steps to connect local businesses with loans and other types of emergency financial assistance to help them keep staff employed, pay rent, and otherwise stay afloat.

The City can also help businesses recover and grow through the billions of dollars it spends each year on commodities, professional services, and construction. For years, the City has administered a range of programs to provide contracting opportunities to local businesses, small businesses, and businesses owned by women and people of color.

- The Business Inclusion Program (BIP) uses an outreach-based approach that is intended to facilitate the development of business partnerships between prime contractors competing for City contracts and potential subcontractors who meet specific demographic or business requirements.

- The City’s local business preference programs offer bid discounts for firms based in Los Angeles County.

The overall design – and limitations – of the City’s efforts are shaped by its highly decentralized procurement framework, and legal requirements set forth in the California State Constitution and City Charter.

This report evaluates the City’s current approach and identifies ways that the City can use its contracting authority to invest procurement dollars in local, small, and disadvantaged businesses in Los Angeles. We concluded that the City should do more to harness its purchasing power to build an inclusive contracting community that fosters improved economic outcomes for Los Angeles businesses.

The City is Unable to Accurately Measure the Impact of BIP

BIP was established in 2011 through Mayoral Executive Directive 14. BIP brings under one umbrella several business development initiatives that are intended to address contracting equity issues. The City issues or recognizes a variety of business certifications based on demographic characteristics (e.g., race, gender, disabled veteran) or business criteria (e.g., annual revenue, location of principal office, number of employees). The certifications are intended to acknowledge the challenges these businesses face when competing for government contracts.

While the federal government and some state and local government agencies outside of California can develop race- and gender-conscious contracting programs to help women and people of color participate in government contracting, the City of Los Angeles is currently unable to develop programs using a similar approach. Proposition 209 (1996) amended the California Constitution and prohibited public agencies in California from using gender and race as a factor in contract awards.

However, there may be opportunities to implement race- and gender-conscious procurement programs in the future. State legislators recently voted to place a ballot measure (ACA 5) before voters in November 2020 which – if approved – would repeal Proposition 209. Revisions to the City Charter to allow race and gender as a factor in contracting would also be needed, which requires citywide voter approval. In addition, the City would need to demonstrate contracting disparities before developing a narrowly tailored program to remedy those issues.

In anticipation of the potential repeal of Proposition 209, the Mayor issued Executive Directive 27, which requires departments to develop Racial Equity Plans, and initiates a citywide review of hiring and contracting data to identify racial disparities. The City Council has also introduced motions directing departments to explore new ways to support the inclusion of disadvantaged businesses in City contracting. While these are positive first steps, the City needs to address fundamental weaknesses in its business inclusion strategy.

Inclusion through outreach – At the core of BIP is the requirement for prime contractors competing for City business to carry out a series of outreach tasks to notify certified businesses about potential subcontracting opportunities. Prime contractors must demonstrate that they made a “good faith effort” in carrying out these tasks, including any negotiations with certified businesses who seek to fulfill a useful subcontracting role.

Prime contractors communicate with potential subcontractors using the Los Angeles Business Assistance Virtual Network (LABAVN), the City’s online portal for advertising contracting opportunities and facilitating outreach between vendors. Prime contractors can be disqualified from a procurement for failing to conduct BIP outreach, but the City cannot compel them to partner with firms owned by women and people of color because of Proposition 209.

The BIP model – mandatory outreach and voluntary subcontracting partnerships – inherently limits the reach of the program. Prime contractors who believe that working with certified firms will make their bids less competitive – or see subcontracting dollars paid to certified businesses as foregone profits – are unlikely to bring in subcontractors. A frequent criticism of the program is that some prime contractors make “good fake efforts” without any intention of partnering with certified businesses.

Moving forward, the City should weigh its options as it relates to the long-term direction of BIP and its potential to impact the local economy. But the City’s ability to make informed decisions about BIP is impeded by longstanding procurement challenges. Specifically, the City must discern the extent to which program design and implementation factors have contributed to BIP’s shortcomings.

BIP program management issues – Since its inception, BIP has been hampered by the City’s decentralized procurement framework which delegates authority to each City department to manage its own procurement processes and records. This makes ensuring departmental compliance with BIP requirements – and measuring the program’s impact – extremely difficult.

- Lack of a dedicated program manager – No single department or City official was actively managing the BIP program until the City hired its first Chief Procurement Officer (CPO) in 2018. The CPO plans to modernize BIP outreach with the eventual replacement of LABAVN. The new application is intended to operate as a virtual marketplace that will improve the ability of firms to match with one another and develop new business relationships. However, improving BIP is one of several procurement reform initiatives under the CPO’s purview. Furthermore, with a relatively small team of just three analysts, the CPO likely lacks sufficient resources to monitor on an ongoing basis departments’ compliance with BIP outreach and data reporting requirements.

Contracting managers in City departments are still responsible for day-to-day issues related to BIP administration, including evaluating prime contractors’ “good faith effort” and monitoring whether prime contractors are following through with subcontracting commitments.

- No citywide analysis of BIP participation data in recent years – City departments are required to report BIP participation rates on a quarterly basis to the Office of the Mayor and a Small and Disabled Veteran Business Procurement Advisory Committee. But the Advisory Committee is now defunct, and departments do not regularly report business inclusion data.

The City also lacks a centralized procurement management system and departments have been inconsistent in how they track and report BIP data. As a result, neither City officials nor the business community can accurately assess the rates at which certified businesses are participating in City contracts. This makes it difficult to determine which types of businesses are being left out of contracting opportunities, and whether the City needs to engage certain businesses for additional outreach or capacity development.

Improvements in these areas will give the City the tools and information it needs to make larger decisions about the future of BIP.

Local and Small Business Participation in City Contracts

Proposition 209 did not limit the City’s ability to implement contracting initiatives that consider race- and gender-neutral factors like business location and size. The City Charter authorizes the City to provide bid preferences to businesses located in the State of California and Los Angeles County.

Fortunately, the City has policies and programs in place which lay a foundation for improving its ability to connect local firms to contracting opportunities. The City currently offers limited bid preferences for certified Local Business Enterprises and Small Local Business Enterprises. However, there are opportunities to include more local small businesses in the City’s procurement enterprise.

Implementation of targeted subcontracting minimums for large contracts – The City should consider requiring prime contractors to include certified local small businesses as subcontractors by establishing a minimum participation rate for each contract. This strategy would ensure that local small businesses partner with larger firms and participate in contracts which they would not normally be able to compete for as a prime. This could create new opportunities for local small businesses – many of which are owned by women, people of color, disabled veterans, and other groups.

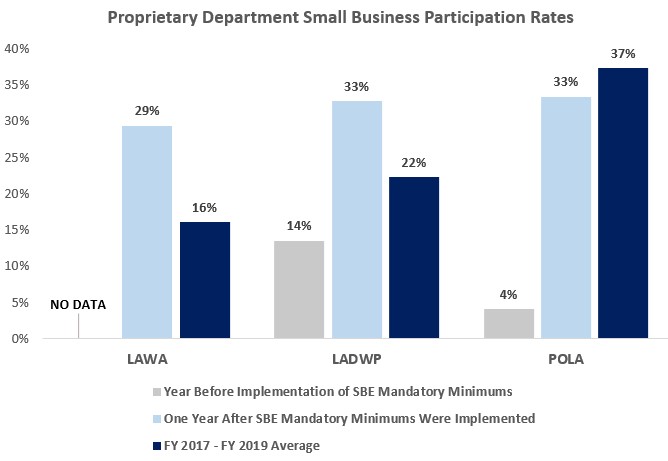

The City’s proprietary departments – Los Angeles World Airports (LAWA), Port of Los Angeles (POLA), and Department of Water and Power (LADWP) – have taken this approach. The proprietary departments develop individually tailored mandatory small business participation rates for each contract. As a result, proprietary departments have increased the number of small businesses participating in their contracts.

An important factor in the implementation of these programs is that each proprietary department has a full-time procurement staff consisting of professionals with specific industry knowledge to set local and small business participation requirements on a contract-by-contract basis. Scaling up this approach to Council-controlled departments will require decisions about which departments have the necessary procurement expertise to successfully implement the initiative.

The Port of Los Angeles, which was the first department to implement such a strategy, has seen the greatest increase in small business participation. In 2006, the year prior to the implementation of mandatory small business minimums, the Port’s small business participation rate was just 4 percent. Since implementing the program, participation by small businesses has increased considerably – an average of 37 percent of the Port’s contracting dollars went to small businesses during the last three fiscal years. Both the Department of Water and Power and Los Angeles World Airports have seen similar trends with their programs.

Although these trends represent a limited sample size and further in-depth analysis is required before larger conclusions can be drawn, they are a promising indicator of what might be possible if the Council-controlled departments emulated the proprietary departments’ approach. In implementing mandatory small business subcontracting minimums, the City should carefully monitor participation by firms owned by women and people of color to ensure the program does not negatively impact participation by those groups.

Mandatory small business inclusion would provide vitally important opportunities to small businesses. In FY 2019, City departments spent approximately $2.2 billion on contracting (excluding proprietary departments). If the City for example had achieved a 25 percent small business participation rate, it would have resulted in an estimated $550 million in contracting commitments to small businesses. A 15 percent participation rate would have resulted in $330 million for small businesses.

Using mentorship programs to help small businesses gain experience and grow – The City should also seek to develop mentorship programs that help small businesses grow, and eventually develop sufficient capacity to compete as prime contractors. Specifically, the City could consider the development of a mentor-protégé program. This type of program would require prime contractors competing for large City contracts to develop a plan specifically outlining how they will mentor and provide technical training and support to one or more small businesses.

The goal of mentorship programs is to help small businesses gain skills in areas where they may lack expertise, such as accounting or marketing. In addition, prime contractors that have previously done business with the City can help smaller firms navigate the complex contracting processes of the City and other government agencies. Effective mentorship by prime contractors would be an important step in helping small and emerging firms become more competitive.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Now is the time for the City to improve its contracting approach so it can help the local economy recover and grow. The recommendations in this report are intended to provide City Policymakers and the Chief Procurement Officer with the tools they need to make decisions about the future of BIP, and build on existing efforts to use the City’s contracting dollars to support as many local small businesses as possible.

Recommendation #1

Implement program changes through executive or legislative action that provides departments with clear guidance about program goals, roles and responsibilities, processes, and reporting requirements. At minimum, these reforms should:

- identify or establish a City department or working group and provide them with the resources and authority necessary to effectively monitor and enforce BIP requirements;

- redesign the prime contractor outreach process to promote streamlined and meaningful outreach to certified firms, including small businesses, local businesses, and businesses owned by women and people of color; and

- establish controls ensuring the standardization of BIP data collection and reporting by City departments and regularly publish or make that data available via a public dashboard.

Recommendation #2

Consider expanding the BIP program to include new benefits for small businesses seeking to grow and conduct business with the City. Specifically, the City should establish pilot programs to:

- require mandatory local small business participation for larger City contracts when subcontracting opportunities are identified; and

- create a mentor-protégé program where more experienced prime contractors are required or incentivized to provide technical training and guidance to smaller firms.

The City spends billions of dollars each year on goods and services from the private sector to support a wide range of government operations. Given this substantial purchasing power, it is in the City’s best interest to leverage its contract spending to support the local economy and hardworking Angelenos. Investing in local businesses has taken on new importance in light of the emerging economic downturn, which will have a lasting impact on many local businesses.

Unfortunately, the disruption caused by COVID-19 has devastated businesses and laid bare many of the existing inequities in communities across Los Angeles. Small businesses and businesses owned by women and people of color are especially vulnerable because they already face institutional barriers and it can be difficult to access capital from banks and other sources.

Finding ways to connect vulnerable businesses to loans and other forms of assistance is critical, but it is also important to identify longer-term solutions to help businesses recover and grow. At the local level, the City has programs and policies in place that are intended to:

- connect entrepreneurs with business development resources and technical assistance;

- create incentives that make it easier for businesses located in Los Angeles and surrounding areas to do business with the City; and

- increase outreach to businesses owned by women, people of color, disabled veterans, and other groups so that they are aware of City contracting opportunities.

Given the economic damage caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, it is critical that the City maximize the impact of its purchasing power and contracting tools. We evaluated the City’s current approach and identified practical strategies that can improve the City’s ability to circulate contracting dollars throughout the local economy and help Los Angeles businesses and residents get back to work.

The City’s Procurement Framework

Unlike other large local governments, such as Los Angeles County, the City and County of San Francisco, the City of Los Angeles has a highly decentralized procurement structure. Varying levels of procurement authority and functions are delegated across City departments, and many of the processes associated with the contracting lifecycle are not automated.

The City has taken steps to reform many aspects of its overall procurement enterprise. The City hired its first Chief Procurement Officer (CPO) in 2018 and is focusing on streamlining City procurement processes for all businesses. In addition, the Department of General Services (GSD), which manages commodities purchases, has implemented a new procurement system so it can better manage the procurement lifecycle for goods, materials, and equipment. But the overall decentralized procurement model remains, which impedes development of a business-friendly contracting environment and standardized program management.

City departments procure many types of goods and services, ranging from heavy equipment for the Bureau of Street Services, to specialized information technology consulting to help modernize the City’s information systems. City contracts with private businesses typically fall into one of three categories – construction, personal (i.e., professional) services, and commodities.

| Construction

|

Contracts covering the construction and retrofits of City infrastructure and facilities |

| Personal (i.e., Professional) Services | Contracts for services, such as legal support, medical services, specialized consulting, and janitorial services, among others |

| Commodities | Contracts covering the procurement of goods such as supplies, materials, equipment, and vehicles |

When a City department identifies a contracting need, it develops a solicitation that includes information such as minimum product specifications, minimum vendor qualifications, and the scope of services needed. Most City contracts go through an open and competitive bidding process. All City departments advertise opportunities via the Los Angeles Business Assistance Virtual Network (LABAVN), which is the City’s central, online portal for managing bid solicitations.

Business Assistance Programs Offered by the City

The City offers several programs aimed at helping businesses. Some of these programs are intended to help companies do business with the City as a contractor, while others are designed to help entrepreneurs navigate the hurdles and complexities of starting and running a business.

| COVID-19 Small Business Emergency Loan Program

(Economic and Workforce Development Dept.) |

During the COVID-19 crisis, the City has administered microloans to eligible small businesses within the City which serve as a lifeline as those businesses cope with unexpected financial stress and lost revenue. |

| BusinessSource Centers

(Economic and Workforce Development Dept.) |

Ten of these resource centers are located throughout the City offering free or affordable business services, including business development consulting, financing solutions, training, and tax consulting. |

| Small Business Loan Program

(Economic and Workforce Development Dept.) |

This program offers loans to small businesses that might otherwise be unable to obtain loans from private lenders. Of the jobs created by the loan recipient, 51 percent must be made available to low and moderate-income individuals. |

| Restaurant and Small Business Express Program

(Dept. of Building and Safety) |

This program helps businesses open on time and on budget. Participating businesses are assigned case managers to facilitate the permitting, construction, and inspection process, which includes multiple departments. |

| Contractor Development and Bonding Program

(City Administrative Officer) |

This program helps small businesses compete for City contracting dollars. Participants receive a case manager to consult on capacity and business development needs and are also eligible for bond (insurance) assistance. |

| Small Business Academy

(Dept. of Public Works, LAWA, LADWP, POLA) |

This seven-session academy teaches small businesses about marketing, financing, insurance, and other business development topics. Participants also learn about the City contracting process and how to compete for contracts. |

As the economy grapples with a pandemic-induced recession, the City’s efforts to help vulnerable businesses have taken on a new level of urgency. For years, the City has administered a range of programs to provide contracting opportunities to local and small businesses and businesses owned by women and people of color. The overall design – and limitations – of these efforts are shaped by the City’s decentralized procurement framework and legal requirements set forth in the California State Constitution and City Charter.

While the federal government and some state and local government agencies outside of California can develop race- and gender-conscious contracting programs to help women and people of color participate in government contracting, the City of Los Angeles is currently unable to develop programs using a similar approach. Proposition 209 (1996) amended the California Constitution and prohibited public agencies in California from using gender and race as a factor in contract awards.

However, there may be opportunities to implement race- and gender-conscious procurement programs in the future. State legislators recently voted to place a ballot measure (ACA 5) before voters in November 2020 which – if approved – would repeal Proposition 209. Revisions to the City Charter to allow race and gender as a factor in contracting would also be needed, which requires citywide voter approval. In addition, the City would need to demonstrate contracting disparities before developing a narrowly tailored program to remedy those issues.

In anticipation of the potential repeal of Proposition 209, the Mayor issued Executive Directive 27, which requires departments to develop Racial Equity Plans, and initiates a citywide review of hiring and contracting data to identify racial disparities. The City Council has also introduced motions directing departments to explore ways to support the inclusion of disadvantaged businesses in City contracting. While these are positive first steps, the City needs to address fundamental weaknesses in its business inclusion strategy.

BIP was established in 2011 through Executive Directive 14 (ED14).[1] BIP is a broad effort which aims to increase contracting transparency and make it easier for local businesses, small businesses, and businesses owned by women and people of color to participate in City contracting.[2] The primary goal of ED14 was to establish a single web portal that would allow any business to search for City contracting opportunities. The web portal would also serve as a platform allowing businesses to communicate with one another to make it easier for firms to develop subcontracting partnerships.

ED 14 represented a significant change to how departments advertised their contracting opportunities by mandating the following:

- all departments must use the City’s Los Angles Businesses Virtual Network (LABAVN) to advertise contracts, creating a one-stop solution for advertisements;

- firms competing for contracts must reach out to a minimum number of small business, local businesses, and businesses owned by women and people of color to discuss potential subcontracting opportunities; and

- firms competing for contracts must reach out to potential subcontractors using LABAVN’s messaging portal, which automatically documents their outreach efforts.

The outreach requirement – commonly referred to as “good faith effort” or GFE – is intended to ensure prime contractors take reasonable steps to develop subcontracting partnerships with businesses that typically face institutional barriers and higher operating costs in comparison to other regions in the United States. The intended targets for GFE outreach are firms registered in LABAVN with specific business certifications.

Eligible businesses can become certified with one of several designations. The certifications recognized by the City have been established through a series of City Council actions, Mayoral Executive Directives, and federal laws intended to help level the playing field for all businesses. As shown in the table below, most of these certifications are race- and gender-neutral, and have certification criteria based on business size, revenue, and location.

| Certification | General Business Requirements | Race/Gender Neutral? |

| Minority Business Enterprise (MBE) | At least 51% owned and controlled by minority individuals | No |

| Women Business Enterprise (WBE) | At least 51% owned and controlled by women | No |

| Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (DBE) | At least 51% owned and controlled by socially and economically disadvantaged minority individuals[3] | No |

| Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Business Enterprise (LGBTBE) | At least 51% owned and controlled by lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender persons | No |

| Small Business Enterprise (SBE) | A principal office in CA, and 3 years gross receipts averaging less than $15 million for construction firms, or less than $7 million for non-construction firms | Yes |

| Emerging Business Enterprise (EBE) | A principal office in CA, and 3 years gross receipts averaging less than $5 million | Yes |

| Disabled Veteran Business Enterprise (DVBE) | At least 51% owned and controlled by disabled veterans living in CA and headquartered in CA | Yes |

| Local Business Enterprise (LBE) | At least 50 full time employees headquartered, or spending at least 60% of their total hours within LA County[4] | Yes |

| Small Local Business (SLB) | A principal office within LA County, and 3 years gross receipts averaging less than $3 million | Yes |

| Small Business Enterprise – Proprietary Departments (SBE-P) | Based on U.S. Small Business Administration criteria for each NAICS classification or 3 years gross receipts averaging less than $15 million (whichever is greater)[5] | Yes |

| Very Small Business Enterprise – POLA (VSBE) | A principal office in CA and 3 years gross receipts averaging less than $5 million or a small business manufacturer with 25 or fewer employees | Yes |

There are approximately 6,000 certified businesses listed in LABAVN, and an individual business can possess multiple certifications. For example, a woman-owned law firm located in Los Angeles with gross receipts of less than $7 million may be certified as WBE, DBE, SBE, LBE, and SBE-P. Within the City, the Public Works Bureau of Contract Administration (BCA) is responsible for reviewing applications and issuing certifications. The City also recognizes certain certifications issued by federal, state, and local agencies.

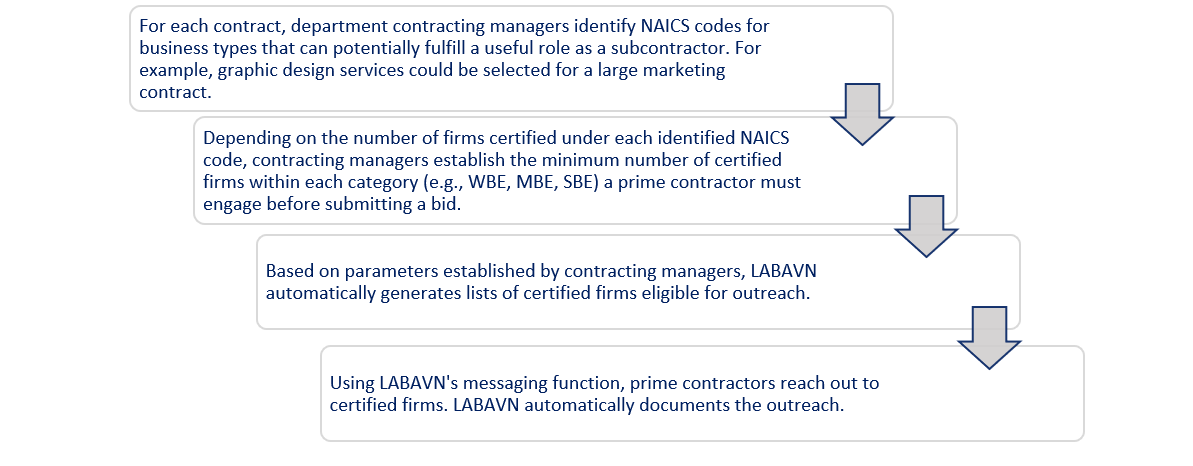

Certifications play a central role in helping firms learn about subcontracting opportunities. The process by which certified businesses receive notifications about subcontracting opportunities is described below.

Contracting managers are tasked with determining whether the contractors met the outreach steps described above, in addition to other activities. To be deemed responsive, prime contractors must demonstrate that they have successfully completed the following:

- attend pre-bid/proposal meeting(s);

- identify sufficient work for subcontracting;

- send written notices to potential subcontractors notifying them of the opportunity;

- provide information to potential subcontractors about the availability of relevant plans/specifications;

- negotiate in good faith with subcontractors that submit bids/proposals; and

- offer assistance to subcontractors in obtaining bonds, lines of credit, and insurance required by the City or prime contractor.

Failure to comply with these requirements will render a bid or proposal nonresponsive and result in its rejection but the City cannot compel prime contractors to partner with firms owned by women and people of color because of Proposition 209.

Although the City can enforce its outreach requirement by rejecting bids or proposals from contractors that fail to comply, measuring the impact of outreach conducted through BIP would help policymakers improve the program. The City must consider whether facilitating communication between the prime contractor and certified businesses is enough to expand the number of firms participating in City contracts and create a sustainable boost to the local economy.

The City is Unable to Accurately Measure the Impact of BIP

During this review, we identified several issues related to the BIP outreach process and the City’s implementation of the program that need to be addressed moving forward. While some of the program management concerns we identified are largely the result of the City’s decentralized procurement framework, other issues indicate that larger changes may be needed to help BIP achieve its intended outcomes.

Inclusion through outreach – Because the City does not compel prime contractors to partner with certified businesses, the outreach process is regarded by some contracting managers as superficial – and most likely ineffective. Ultimately, prime contractors who see contracting equity as an added value will find ways to partner with certified businesses, while prime contractors who see subcontracting dollars paid to certified businesses as foregone profits will not.

All programs require ongoing evaluation and refinement to ensure that they are achieving their intended outcomes. Moving forward, the City should weigh its options as it relates to the long-term direction of BIP. This process requires the ability to discern the extent to which program design and implementation factors have contributed to its shortcomings. Unfortunately, the City’s ability to make informed decisions about BIP is impeded by longstanding citywide procurement challenges.

Lack of a dedicated program manager – Each City department’s procurement needs are different. Large departments such as BCA have experienced procurement staff whose primary task is to oversee the contract lifecycles of multimillion-dollar contracts. Smaller departments that manage contracts less frequently may assign contracting manager responsibilities on an ad hoc basis.

The City’s decentralized procurement model impacts citywide efforts to consistently administer BIP, and the procurement process in general. Prior to the appointment of the CPO, BCA (which manages public works contracts) served as a de facto contracting and BIP advisor to City departments. However, BCA was not responsible for managing BIP and did not have authority to instruct other City departments to make improvements.

The CPO, who now serves as the BIP program business owner, plans to modernize BIP outreach with the eventual replacement of LABAVN. The new application is intended to operate as a virtual marketplace that will improve the ability of firms to match with one another and develop new business relationships. However, BIP improvements is one of several procurement reform initiatives under the CPO’s purview. Furthermore, with a relatively small team of just three analysts, the CPO likely lacks sufficient resources to monitor departments’ compliance with BIP outreach and data reporting requirements on an ongoing basis.

Many of the City’s peers, including Los Angeles County, the City and County of San Francisco, and the City of San Diego, have citywide procurement management departments that are responsible for either centrally managing purchasing and contracting, or acting as a procurement support unit to other departments. These departments are typically responsible for managing similar contracting equity programs. Without such a department in the City of Los Angeles, consistent implementation and monitoring of BIP will remain difficult.

Inadequate data collection and reporting – ED14 requires departments to report BIP participation rates on a quarterly basis to the Office of the Mayor and a Small and Disabled Veteran Business Procurement Advisory Committee. However, this advisory committee is now defunct, and the City does not regularly report citywide business inclusion data.

Even if there was centralized leadership in place to oversee the program, accurate and timely data collection would be nearly impossible. The City does not have a centralized procurement management system and departments have been inconsistent in how they track and report BIP data.

As a result, neither City officials nor the business community can adequately assess the rates at which certified businesses are participating in City contracts. This makes it difficult to determine which types of businesses are being left out of contracting opportunities, and whether the City needs to target certain businesses for additional outreach or capacity development.

The most recent effort by the City to develop a comprehensive BIP progress report was in response to a request by the City Council in 2016. BCA was tasked with compiling data from other departments because the City lacked a centralized procurement system and dedicated BIP manager. Although BCA generated the report, the reliability of the self-reported data is low, and some departments did not provide any information.

While the City can take steps to create an environment where certified firms are more aware of business opportunities, a fundamental weakness of BIP is its reliance on prime contractors working in good faith to develop subcontracts. Improvements to program governance and data collection will give the City the tools and information it needs to make larger decisions about the future of BIP.

[1] The City’s first women and minority business enterprise initiative for City contracting was established in a 1983 Executive Directive.

[2] Though formally exempt from the program, the directive requested that the City’s proprietary departments – Los Angeles World Airports, Port of Los Angeles, Department of Water and Power – implement similar programs and policies.

[3] Federal DBE guidelines recognize women, African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Native Americans, Asian-Pacific Americans, and Subcontinent Asian-Pacific Americans as socially and economically disadvantaged. Other individuals can also qualify as socially and economically disadvantaged on a case-by-case basis.

[4] POLA has a separate Local Business Enterprise certification which includes businesses headquartered within Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, and Ventura Counties.

[5] The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) is the classification standard used by federal agencies for classifying business establishments. The system facilitates the collection, analysis, and publication of statistical data related to the U.S. economy.

While Proposition 209 strictly prohibits the City from providing any kind of contracting preference to firms based on race or gender, it does not restrict cities from implementing race- and gender-neutral contracting initiatives that consider factors like business location, size, and revenue.

The Board of Public Works is testing what is known as “community-based contracting”, where large public works projects are broken into a series of smaller contracts so that small, locally-based firms have the ability to compete for the opportunities. While this and other initiatives are a good start, the City can do much more to promote the inclusion of local small businesses in City contracts.

Fortunately, the City already has a framework in place that can help the City expand existing efforts to help local and small businesses. New small business initiatives could create fresh opportunities for local small businesses, many of which are owned by women, people of color, disabled veterans, and other groups.

The City Charter generally requires departments to award contracts to the lowest responsible bidder, but it does allow the City to provide preference to firms based in the State of California and Los Angeles County. Excluding certifications used exclusively by proprietary departments, the City has three small business certifications restricted to firms located in California or Los Angeles County. Those certifications include:

- Small Business Enterprise;

- Emerging Businesses Enterprise; and

- Small Local Business Enterprise.

The City currently offers bid preference for two certification types – Local Business Enterprises and Small Local Business Enterprises.[6] The City Council established both programs recognizing that firms operating in the Los Angeles area face higher labor and operating costs compared to neighboring states and other counties within California. In addition to receiving additional outreach through BIP, the City’s procurement process affords firms certified under these programs with an advantage when they are competing for City contracts.

| Local Business Preference | For contracts that are $150,000 or greater, Local Business Enterprises (LBE) shall receive preference in the form of an eight percent reduction in the bid price or an eight percent increase in the proposer’s score. Non-LBE firms can receive preference points of up to five percent, based on amount of work to be performed by LBE subcontractors.[7] |

| Small, Local Business Preference | For contracts that are $100,000 or less, SLB bidders and proposers shall receive a preference in the form of a ten percent reduction in the bid or proposal price. |

While these programs are a good initial step in encouraging the investment of contracting dollars within the local economy, the City should consider expanding local preference programs to ensure small businesses are participating in City contracts.

Implementation of Targeted Subcontracting Minimums for Large Contracts

The City should consider requiring prime contractors to include local small businesses as subcontractors by establishing a minimum participation rate for each contract. This strategy would ensure that local small businesses partner with larger firms and participate in contracts which they would not normally be able to compete for. For each contract, departments would set minimum small business participation levels based on multiple factors, including:

- the type of contract and the pool of available small businesses based on NAICS data;

- the number of certified firms available to perform the work in LABAVN; and

- small business participation rates for similar projects in the past.

For example, if a department is seeking bids for the construction of a new building at an estimated cost of $1 million, the department could require prime contractors competing for the project to meet a small business participation rate of 20 percent of the contract value. If the prime contractor’s bid shows that 20 percent of the work will be performed by a small, locally owned construction firm, the prime contractor will have met the participation requirement. If the prime contractor wins the contract, the small business would perform $200,000 (20 percent) worth of services for the prime contractor. In the event a prime contractor fails to meet small business subcontracting commitments, the firm could be subject to financial penalty.

This strategy has already proved successful at the City’s three proprietary departments (POLA, LAWA, and LADWP). Each department’s respective Board of Commissioners established a mandatory small business participation program to increase support for small businesses and increase the number of firms conducting business with the department.

Each proprietary department sets mandatory small business participation minimums for construction and personal services contracts. POLA, which was the first to establish their small business program, has seen the greatest increase in participation levels as a percentage of total contract awards. POLA’s small business participation rate averaged 37 percent from FY2017 through FY2019. Both LADWP and LAWA have seen similar trends with their programs.

Although these trends represent a limited sample size and further in-depth analysis is required before conclusions can be drawn, they are a promising indicator of what might be possible if the Council-controlled departments emulated the proprietary departments’ approach. It is important to note that the small business size threshold (based on annual gross receipts) for proprietary departments is larger than the threshold for the City’s Small Business Enterprise certification.[8]

Mandatory small business inclusion could provide important opportunities to local and small businesses. In FY2019, City departments spent about $2.2 billion on contracting (excluding LAWA, LADWP, and POLA). If the City for example had achieved a 25 percent small business participation rate, it would have resulted in an estimated $550 million in contracting commitments to small businesses. A 15 percent participation rate would have resulted in $330 million for small businesses.

An important issue to consider is that each proprietary department has a full-time procurement staff consisting of professionals with specific industry knowledge to set local and small business participation requirements on a contract-by-contract basis. Scaling up this approach to Council-controlled departments will require decisions about which departments have the necessary procurement expertise to successfully implement the initiative.

In implementing mandatory small business subcontracting minimums, the City would also need to carefully monitor participation by firms owned by women and people of color to ensure the program does not negatively impact participation by those groups. The City would also need to ensure that departments develop reasonable small businesses participation requirements, and all departments are consistent in how they develop participation rates. Alternatively, it may also be beneficial for a single office to be responsible for establishment of participation rates for all City contracts to ensure the criteria is applied consistently citywide.

Using Mentorship Programs to Help Small Businesses Gain Experience and Grow

Although the City already administers programs which provide direct training and development services to small and disadvantaged businesses – such as the Contractor Development and Bonding Program and the Small Business Academy – there are opportunities to leverage the expertise and resources of large City contractors in order to assist small businesses in need of developmental assistance. This assistance could come in the form of a mentor-protégé program.

The goal of a mentor-protégé program is to help small and emerging firms develop the skills and capabilities that allow them to successfully compete as prime contractors. In a mentor-protégé program, the City would require prime contractors competing for large City contracts to develop a mentorship plan specifically outlining how it will mentor and provide technical training and support to one or more small businesses.

Specifically, prime contractors would need to develop a formal plan to:

- provide mentorship, training, and technical assistance in areas such as finance, insurance, organizational development and design, and human capital;

- create business outreach and networking opportunities; and

- incorporate protégés into future subcontracting roles.

Mentorship could extend to one of several certification types, including Emerging Business Enterprises, Small Business Enterprises, and Small, Local Business Enterprises. Other large public agencies have instituted mentor-protégé programs for disadvantaged or small businesses. LA Metro for example requires prime contractors competing for contracts valued at more than $25 million to submit a mentorship plan for certified Disadvantaged Business Enterprises, Small Business Enterprises, and Disabled Veteran Business Enterprises.

The City of San Francisco also manages a mentor-protégé program. Rather than requiring prime contractors to provide mentorship opportunities, both mentors and protégés apply to be members of the program. Mentors must have experience as a successful prime contractor, while firms with the City’s Micro-Local Business Enterprise certification are eligible to participate as protégés. As an incentive for prime contractors to serve as mentors, the City of San Francisco will waive prime contractors’ good faith outreach requirements for a period of two years.[9]

The City should continue to encourage large firms to mentor small businesses and entrepreneurs within the local community. Not only does mentorship and capacity development guidance help foster small business growth, it paves the way for future business relationships and better positions small firms to eventually compete as a prime contractor.

[6] The City Council established the Local Business Preference Program by ordinance in 2011 and the Small, Local Business Program by ordinance in 2001.

[7] The City Council has approved changes to the Local Business Preference Program (Council File 18-0255). Under the proposal, the Small, Local Business Preference Program would be merged into the Local Business Preference Program. Local Business Enterprises would receive an eight percent bid preference, and those also holding a Small Business Enterprise certification would receive an additional preference of two percent. Small, Local Business Enterprises competing for contracts valued at $150,000 or less would receive a ten percent bid preference.

[8] The Small Business Enterprise-Proprietary certification is tied to specific size standards set by the U.S. Small Business Administration for each NAICS code.

[9] The City of San Francisco requires firms competing as prime contractors to reach out to and negotiate in good faith with firms holding the city’s Local Business Enterprise certifications.

Now is the time for the City to improve its contracting approach so it can help the local economy recover and grow. The recommendations in this report are intended to provide City Policymakers and the Chief Procurement Officer with the tools they need to make decisions about the future of BIP, and build on existing efforts to use the City’s contracting dollars to support as many local small businesses as possible.

Recommendation #1

Implement program changes through executive or legislative action that provides departments with clear guidance about program goals, roles and responsibilities, processes, and reporting requirements. At minimum, these reforms should:

- identify or establish a City department or working group and provide them with the resources and authority necessary to effectively monitor and enforce BIP requirements;

- redesign the prime contractor outreach process to promote streamlined and meaningful outreach to certified firms, including small businesses, local businesses, and businesses owned by women and people of color; and

- establish controls ensuring the standardization of BIP data collection and reporting by City departments and regularly publish or make that data available via a public dashboard.

Recommendation #2

Consider expanding the BIP program to include new benefits for small businesses seeking to grow and conduct business with the City. Specifically, the City should establish pilot programs to:

- require mandatory small business participation for larger City contracts when subcontracting opportunities are identified; and

- create a mentor-protégé program where more experienced prime contractors are required or incentivized to provide technical training and guidance to smaller firms.